- 资质:

- 评分:

1分 2分 3分 4分 5分 6分 7分 8分 9分 10分 0分

- 印象:

- 经营时间:

- 展厅面积:

- 地 区:上海-普陀-莫干山路M50艺术区

A SHAMAN IN BEIJING--The Work of Cang Xin

2011-04-15 11:32:46

I never expected to see cutting-edge contemporary Chinese art and fading propaganda from the Cultural Revolution on the same wall. Yet at gallery798,a former Beijing military factory now an art complex, I saw a digitally manipulated image of a nude below giant red block-prink Chinese characters reading:“Mao Zedong live ten thousand years!”Since the radical changes of the part twenty-plus years, it is rare to happen upon writing from the Cultural Revolution---a time when the Chinese government put a violent halt to intellectual and spiritual life.

I walked down the concrete hallway to the studio of Cang Xin to begin a series of interviews. Cang Xin,37,a major figure in contemporary Chinese art, and had exhibitions throughout China and his work has been shown in Japan, Norway, Thailand, France, Italy, Australia, and the United States. In2002, his performance art was part of the Sydney Biennale and in 2004(and 2005)his work was displayed in the exhibition Between Part and Future at the International Center of Photography in New York and the Smart Gallery of the University of Chicago. After schooling in rock and roll, Western philosophy, and oil painting, Cang Xin became an active member of the controversial Beijing-based“East Village”art group in the 1990s, participating in To Add One Meter to an Unknown Mountain, now a “classic”of recent Chinese art. His early work was often confrontational, including his 1994, Virus Series Highest State of the Mundane(Trampling Faces).Here, he used a mold of his face to produce fifteen hundred plaster masks that he placed in a small yard; visitors were invited to walk in, one by one-and crush his image beneath their feet. Now in his late thirties, Cang Xin has turned more towards our relationship to the spiritual. Recently, he has completed several photographic series, including Identity Exchange, in which he dons the clothing of another individual –including a Beijing Opera performer, a farmer, and a prostitute; photographs show him standing next to this person)now only in undergarments)who has been stripped of society’s role. In his visually stunning Union of Man and Sky series, Cang Xin poses naked in a green lotus pond, on a sheet of ice inside a circle of fire, and in the mountains on the border between Sichuan province and Tibet. These works suggest that humans in their original spirit are connected to a natural environment. The artist’s ongoing series, Communication, and his newest work are of particular interest, as we will see.

Inside his studio, Cang Xin tells me he likes the fact that the Cultural Revolution characters remain on the wall. “It gives a sense of the past… of where we came from.” Yet, the inspiration behind Cang Xin’s art can be traced farther into Chinese history and culture-indeed to its very roots.

Cang Xin finds inspiration in the spiritual traditions of Daoism, Buddhism, and shamanism. Daoism may be seen as a spiritual philosophy, a political philosophy, a way of life, a religion, and a practical tradition of meditation and matial arts. It permeates nearly every aspect of Chinese culture, especially art, poetry, and medicine. Mahayana Buddhism, which came to China through India and Tibet, was widespread and influential throughout much of Chinese history and ,in some communities, still flourishes today. Perhaps most important to Cang Xin’s work is shamanism, which many people consider to be the root of religion itself. Cang Xin’s heritage is Manchurian, and shaman traditions flourished in Siberia and Northern China, including amongst Manchu people.

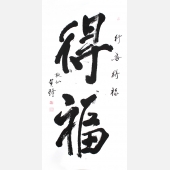

In fact,Cang Xin sees himself as a kind of shaman. In his ongoing photographic project,Communication, he performs the shaman ritual of touching his tongue to myriad objects and the ground beneath symbolic sites. Looking at the images in the series, Cang Xin seems to lick everything in our world-from abird’s head to a gun to a roes to mundane objects like a package of toothpaste and a bottle of mosquito repellent. Many have obvious intellectual themes such as an old Chinese compass(used in Fengshui practice),some of the Five Elements from ancient Chinese thought(fire,wood and water),a miniature body marked with the nodes of Chinese medicine, and elegant calligraphy. Yet on some level, the toothpaste package, the calligraphy, and the fire are all equal in that they are simply things with which the artist may commune.

For each work, the artist has an experience that is photographed; later the iviewer may connect to the artist’s experience or(more likely) have her or his own separate experience. Cang Xin says some of his deepest impressions came licking the scales of a lizard and a snake. When he touched them with his tongue, he sensed“ice-cold meat..and a feeling of darkness overcame me. It was terrifying.”From his description one can decipher a shaman-like process—the use of a material object to reach the irrational, spiritual level. In the photo where his tongue touches drops of water,one cannot tell if the liquid arises from within him or if his tongue approaches the water. Near the end of his tongue is a space of darkness, like a well or a chasm, In the photo with the artist licking the bird’s head,both the bird and the tongue suggest equanimity, as if each felt entirely at home in this unusual position. Cang Xin’s experience of performing, the ritual and viewer’s experience will almost certainly not be the same; both, however,have the potential to exist somewhere between the sensory world and the spiritual.

To understand the relationship of spirituality to Cang Xin’s art,it is worth taking a look at the traditions that influence him. The artist says,“Shamans use special talents to help us communicate with the spiritual world…We are people meat, but spiritually.”According to Daiost thought, all matter is also spiritual, because it originated as Dao.“The Dao gives birth to one. One gives birth to two. Two gives birth to three. And three gives birth to ten thousand things.”(Dao De Jing, verse42,tr.Bill porter)An interpretation of the famous passage is that“one”is original qi(vital energy),“two”is the mutually dependent opposites,yin and yang(the dark, feminine force and the bright, masculine force).and “three”is the merging of original qi with yin and yang. The“ten-thousand things”stand for all objects in the world; each and every material object, therefore, originate from primal qi and Dao. Since Dao is the source of all spirituality, all objects and beings in the world are not only material, but also contain spiritual essence.

Shamans often use the material world, including extreme physical sensation, to enter the spiritual realm. A shaman might commune with a certain piece of the physical world and thereby enter a trance. Others use sense extremes, such as hot and cold, to overcome the material world. I once visited a Buryat shaman in Siberia who places his tongue on scalding hot rocks as a means of entering a state in which he can channel healing spiritual powers. There kinds of traditions predate historical records, and they are at the root of Daoism. The Zhuangzi, anearly Daoist text probably first composed in the fouth century B.C.E.,makes many references to shamans and says of the perfected man,“Fire cannot burn him, water cannot drown him, cold and heat cannot afflict him.”Cang Xin’s art is both homage to and continuation of these traditions.

Cang Xin uses his tongue not just to feel an object, but also to commune with it as a vessel containing spiritual essence. In a famous episode, Zhuangzi and the sophist, Hui Shi, argue whether or not Zhuangzi can “know”the fish swimming in the river below them are happy. The conclusion is more aesthetic than logical-namely that noe may understand the “ten thousand things”if one uses original nature to commune with them. Cang Xin sees the tongue as the bodily expression of original nature: “The tongue is like a child who does not yet understand the world” Yet the tongue is also an organ key to our sense perception.“The tongue is mainly used in three main situations” says Cang Xin. “Talking, tasting, and sex.”In a seeming paradox, it is precisely in doing something deeply sense-based that the shaman transcends the material world. This is precisely because in these traditions, the spiritual is contained within matter.

Cang Xin’s Communication series indirectly grew out of an incident at a large birthday party attended by many in the Beijing art world. That night Cang Xin and some of his friends feuded, but the situation was kept under control. It would have been very costly for the“East Village”group to attract more negative attention from the community. Indeed, they were already becoming notorious and many had spent time in jail, including Cang Xin, who years earlier was arrested(but soon released)for his involvement in the pro-democracy demonstrations leading up to the Tiananmen Square incident. After the rift at the party, Cang Xin worried that his friends thought he was violent. For one year, he bad virtually no contact with society. He explored reconnecting to his world using his tongue to touch household objects: water, light bulbs, candles, razor blades.

Later,Cang Xin began to perform his shaman-like ritual at famous sites. These places are imbued with old spirit-from the people who built them or inhabited them to the events that have taken place there. Perhaps these places best represent the interweaving of spirit and material. In the last few years,Cang Xin has gone to Europe to further his Communication series, performing his rituals in front of such places as the Coliseum in Rome and Parliament in London. Whether he communes with individual objects or the aura of a place itself, the essence it the same: an artist sharing his connection to the world, both as matter and spirit.

In Shaman Tree, a drawing completed in the fall of 2004 ,Cang xin ,moves away from performing rituals, to confronting the spiritual as content. Shaman Tree centers on the image of a craggy tree in an infinite desert, seemingly devoid of any other life. The tree has no actual leaves, but growing on many twigs are images of the artist’s head-as if he were the fruit. On each“fruit”the artist is licking a cockroach. In touching the cockroaches with his tongue, he again becomes a shaman, communing with these creatures. Cang Xin admires the crawling things in the world.“Snakes, scorpions, lizards, cockroaches. These are older than people-these old creatures are imbued with ancient spirit.”Each twig meets each head at the baihui point, a little behind the crown of the head. This is the place identified in some forms of Daoist meditation(lnner Alchemy)where the immortal embryo transcends the body and floats towards heaven. One may interpret a line of spiritual flow the trunk through the branches, twigs, and baihui into his shaman act or from the shaman act back through the tree.

In Shaman Tree, beneath the earth and taking the place of the tree’s foots, is a child screaming. The child is the ideal state of the shaman.“Children have connections to the past and future, ”Cang Xin says. Some experts argue that after age five, the tianmu (Heavenly Eye)close. This Heavenly Eye, imagined between the eyebrows, is referred to in Daoist, Buddhist, and many shaman traditions, as well as in modern qigong. It is considered an “eye”that can see things beyond normal sensory experience-the past, the future,even one’s own internal organs. Many meditation practices and shaman trances are designed to help regain the insight lost after childhood. In this work, the child is the source of the shaman tree.

The piece also invokes ancient Chinese nature and ancestral worship. The miraculous tree exists in what appears to be an otherwise lifeless desert, giving it a flavor of the sacred. We are accustomed to seeing family trees, and the tree may be construed as a genealogy of spiritual masters. This suggests not only the ancestral worship common in early China, but also shaman traditions which involve the passing of shaman talents within a family. The tree is at once object of worship, altar to ancestors, and lineage of shaman.

Although Cang Xin’s mother is not a traditional shaman, the artist believes she has a strong influence on his work. Since his mother was a “landowner”and his father was not, during the Cultural Revolution, as part of what was called the huaqingjiexian (roughly“clearly draw the lines”)policy, his parents were pressured to divorce. At age five he and his brother moved with his mother to factory complex in Hebei Province. While Cang Xin loves his mother dearly, even dedicating his book existence in translation to her, she was mentally unstable and their relationship has been tumultuous.

His mother is Manchu and Cang Xin identifies with that culture. He fells that, in some sense, he follows in her footsteps.“My mom is like a shaman,”says Cang Xin. “Crazy and fierce.”She would take off all her clothes and run around the village, and gained a reputation as “the madwoman.”In a different setting sand for different reasons, the artists of“East Village,”also used to turn about naked; they too were known by many locals as “crazies.”During periods in his life,Cang Xin and his mother talked about spirituality(Buddhism in particular)nearly every day. Despite these connections and the way she may have unconsciously passed a shaman temperament to her son, she does not understand her son’s work.“She says I am unemployed,”he laughs.

Many historians point to nineteenth century Western influence as a core cause of the divide between matter and spirit in Chinese consciousness. An avid reader of Western philosophy and performance theory, Cang Xin by no means wants to reject Western influence; is has been an enormous resource for him. Still, through his work he commits to a healing of the rift between matter and spirit. Cang Xin struggles with the changes in China, many modeled on Western standards. He frets that in modern times changes are so rapid and radical that aspects of Chinese culture are being lost.“From an airplane, Beijing looks like an American city,”he says. At the same time he appreciates the economic boom of the past few decades and the rising living standards, especially for city dwellers. While Cang Xin may travel the world, draw influence from many American and European thinkers, and enter an art market that, even in China, is dominated by foreigners, he searches for self-expression and spiritual insight in the most difficult paradoxes of today’s Beijing and in the deepest roots of his Manchurian culture. In describing the manifold and contradictory influences on his work. Perhaps these is no more appropriate image than my walk through the exhibition hall—surrounded by cutting edge art and Cultural Revolution propaganda, on my way through the former military factory to the art studio of a Manchurian shaman.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术