Art Basel Miami Beach: Where Art and Commerce Come Together and Party I

2011-04-15 12:22:30

AFTER the last multimillion-dollar Yves Klein painting was crated for shipping, the last private Cessna Citation Ultra had lifted off from Opa-locka Executive Airport, the last glasses from the last dinner party at the W Hotel had been cleared and the last of the 46,000 or more people that descended on a convention center on this glorified sand spit for one highly specialized event had departed, one question remained.

What is Art Basel Miami Beach precisely? Is it merely an art-world trade fair, one of scores now scheduled in succession across the planet? Is it, like much else in Miami Beach, just another over-hyped cross-platform marketing opportunity? Is it a pre-Christmas break for global billionaires?

If, as Silvia Venturini Fendi, the Fendi designer, remarked one afternoon at the Standard hotel here, contemporary art collecting is the “new shopping,” then is it not possible that art fairs like Art Basel Miami Beach are in some sense the new malls? As at malls, there are boutique dealers at Art Basel Miami Beach and key anchor tenants and also a food court, albeit one that sells flutes of Champagne. There is an ambient aura of humming prosperity that masks, but just barely, the giddy excitement sparked when people in an acquisitive frame of mind move in packs.

Art fairs emerged in the last decade as an irresistible phenomenon, said Ms. Fendi, who annually sponsors a booth and a design project at Design Miami, an applied-arts fair that piggybacks on Art Basel Miami Beach, “because everybody wants to be a follower, to have the same collection, and to follow the trends.”

Collecting vogues are certainly on view at Art Basel Miami Beach “I tell all my collectors to look at Baselitz again,” Kim Heirston Evans, a prominent art adviser, remarked at a dinner hosted at the Soho Beach House by Stefano Tonchi, the editor of “W” magazine. Ms. Evans was referring to the German neo-expressionist whose cachet, which crested in the late 1980s, is on the rise again, if one can judge from the prominence afforded Baselitz pictures at booths like that of the dealer Michael Werner, where an abstract by the painter, offered for $750,000, was sold for an undisclosed but purportedly much higher sum.

Perhaps more important, though, the fair provides a viewing platform for observing the evolving folkways of that restricted, migratory species that has increasingly come to dominate wealth around the world.

Over the course of the near-decade since the Miami fair made its debut — one year after a planned inaugural edition was scuttled by the 9/11 attacks — this local version of a storied but sober contemporary-arts trade fair held since 1970 in Basel, Switzerland, has offered the opportunity to observe the rampant growth of a once-rarefied activity that just three decades ago was dominated by a small group of collectors and dealers as though it were their own club.

“Everybody knew each other,” said the dealer Angela Westwater, referring to the long-ago 1970s, when she entered the art world on the ground floor, working at the John Weber gallery in a fabled SoHo gallery building at 420 West Broadway. “Not only was it a smaller, more cohesive scene then, but it mixed artists, dancers, sculptors, painters,” Ms. Westwater said. “It wasn’t a fancy scene.”

NOW, in keeping with the altered rules of the game, Ms. Westwater’s Sperone Westwater gallery operates from an eight-story building on the Bowery designed by Norman Foster to her precise specifications. And now, her competition is no longer derived from a select group of downtown familiars but from an almost bewildering roster of players operating on an international stage.

Over 260 dealers took booths at this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach, nearly 40 percent more than were on the roster in the first year of the fair. The most tabloid-famous among them is undoubtedly Larry Gagosian, a gargantuan persona whose big bets and global aspirations have elicited references to him as a “super dealer.”

Yet the droves that descend on Miami Beach the week of the fair carrying suitcases of euros, pounds and yuan are not destined only for Mr. Gagosian’s booth. And they are not limited to home-grown billionaires like the hedge-fund investor Steven A. Cohen, whose budget for art acquisition sometimes seems to rival the G.D.P. of certain small nations. (And whose SAC Capital Advisors recently was served with a broad subpoena from federal authorities investigating insider trading on Wall Street.)

A generation of the new rich from countries like India, Russia, China and Brazil have also gotten in on an activity once pursued largely by wealthy American collectors so discreet that their names seldom appeared in art business journals, let alone gossip columns — people like Burton and Emily Tremaine, Virginia and Bagley Wright or Victor and Sally Ganz, whose collection, quietly amassed over a half-century and for under $2 million, was sold at auction by Christie’s at the end of 1997 for $206.5 million, at the time the largest sum ever realized for a single-owner sale of modern art.

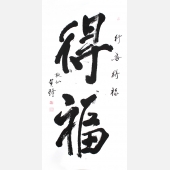

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术