- 资质:艺

- 评分:

1分 2分 3分 4分 5分 6分 7分 8分 9分 10分 1分

- 印象:

- 经营时间:15年

- 展厅面积:300平米

- 地 区:北京-朝阳

常生

- 展览时间:2015-08-10 - 2015-10-12

- 展览城市:北京-朝阳

- 展览地点:NUOART

- 策 展 人:

- 参展人员:

展览介绍

关于谢正莉的新作

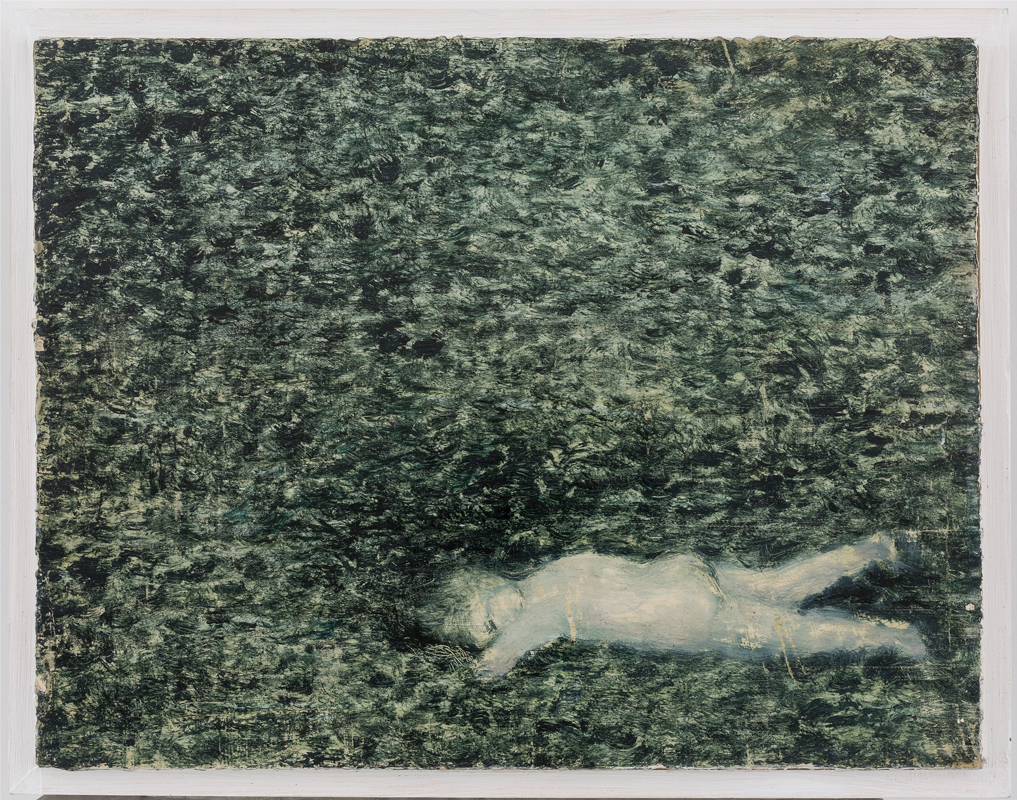

从2010年的个展“谢正莉”,到2012年的个展“形骸”,再到如今的“常生”,谢正莉的绘画展现出年轻人里少见的质感和辨识度。这种辨识度不是来自刻意形成的图像或题材,而是她在不断成长变化的主题中,透露出的独特绘画方式。她先小心地描绘一些想要画出来的东西,然后费力地擦拭它们,再修改。直到画布上的物体被“折磨”透彻,几乎变成自己的影子。这过程不是潇洒自如的,多少有些生涩,甚至有些笨拙,却是她寻找自己想要的某种“神韵”的必经之路。

古人说“画如其人”,而欧洲的学者不喜欢修辞,更讲究词汇,用了画家与画布之间的“亲密性”来形容[1]。所谓“亲密性”,简单来说,就是画家有多大勇气,把自己的情感,自己的技术,毫无掩饰地托付给画布。这个词虽然有点别扭,但用在谢正莉的画上却特别妥当。她不仅是情感和技术,就连全身的力量,还有画画时情绪的波动,也都直白地表现在画布上了。在那些反复摩擦的痕迹里,我们能看到她对哪里是爱惜的,哪里是憎恨的,哪里想改却改不了,却又灵光一现找到解决办法的;甚至她手臂一口气所及的长度,也早就透露在流动的色彩与光影里。她不是技术最出色的年轻艺术家,却是对技术最为诚实的一个。在画画时,她几乎是在拥抱自己的画面。这种坦诚让她的作品始终具备开放和生长性;而且,谢正莉以此为基础,形成了个人的独特气质,并在几年来展现出真实的成长与思考。这一点看似自然而然,却是很多艺术家——包括一些所谓成熟艺术家——所不具备的。实际上,这才是作品能够被真诚地欣赏,梳理,甚至研究的基础。

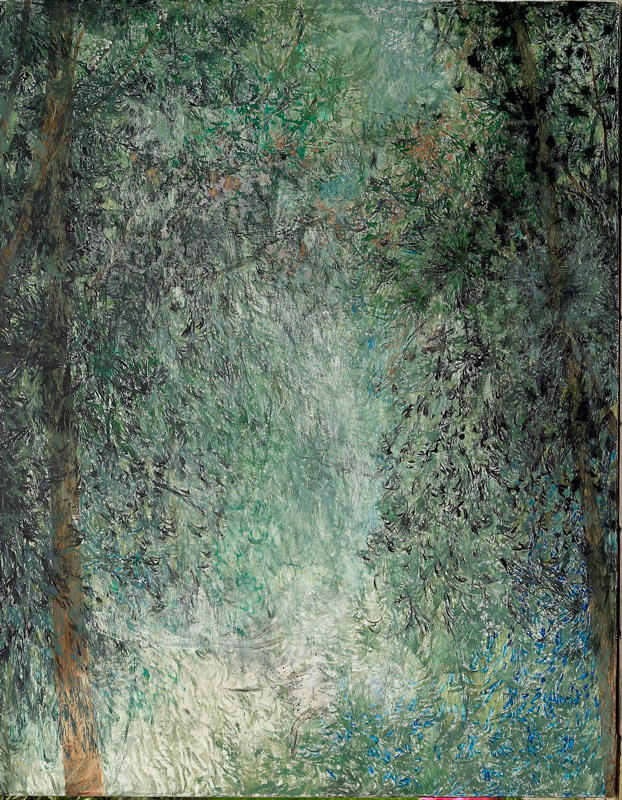

如果说2010年的个展是生涩的,那么2012年的个展“形骸”就展现了她敏锐的感受力。她从自然标本里找到灵感,描绘了被陈列的动物。这些陈列品原本已经死去了,却被她赋予另一种神情,获得了新的生命力。那无关个体动物的生命本身,而是来自造物这个整体的,延绵不绝的气息。这种气息与她作画时充满情感的过程统一在一起,让画布不再是重现图像的表面,而成为生命的延续之地。到那时为止,我们还不太容易看出,“形骸”中的作品究竟在她的创作结构中处于怎样的位置,或者说,来自自然标本的灵感是否只是昙花一现。这次展出的新作品就让担心成为多余。虽然主题变成了花,但作品延续了与自然造物有关的线索;更重要的是,在作品和绘画的层面,同时展现出一贯的,内在而极富韧性的生命力;并让画布——甚至在物理层面本身——与花朵一同绽放了。如果说“形骸”的内容带有静谧的冥思,或者,就像丢勒的著名版画“魅蓝柯丽”一样[2],带有一丝与死亡的未知有关的忧郁;那么本次展出的“常生”系列,就像是在拥抱生命本身的绚丽。画家几乎是用略带任性的热情,把过去的忧郁抛到一旁。

谢正莉出生在重庆,家旁边的公园是她从小玩耍的地方。在她2012年的个展“形骸”结束以后,她也刚好三十岁了。那时,她在公园里偶然看到了和她年纪相同的菊展:第三十届。这似乎是一种暗示。她说:“我生在这里,在这里长大,后来离开,现在又回来了。这些花仍然和小时候一样,是心底最温暖的陪伴。在画了那么多死亡的对象,遥远的骨骸,和生命的告别之后,又看到这些花,才终于真正看到它们……它们在万物凋零的时候绽放。” 这也成为她新作品中菊花形象的源头。它们不是单纯写生而来,而是包含了谢正莉对各种花朵的情感印象。这些印象在记忆中留下真实的痕迹,就像它们在画布上留下若隐若现的痕迹一样。花朵会凋谢,记忆会模糊,但存在过的东西却始终在那里,鲜活的生命力反而被提纯了,变成一种抽象的力量,和画布的力量融为一体。自古以来,爱花的文人很多,陶渊明爱菊花也好,周敦颐爱莲花也好,每个人在花中看到的质地不同,感受也就不同。若说他们有什么共同点,大概只能是“爱花”吧。为何“爱花”“?对花的崇尚,从佛教传入后的“香花供佛”开始有了依据,到宋代随着花瓶成为文房雅器而达到高峰;至于其中的根本原因,大概也只能说是花概括了自然的某种美丽和生命的规律吧。谢正莉并不善于刻意营造文人的雅致气息,却拥有对花的古朴悠长而且刻骨铭心的情感本身。无论古代或当代,在任何时候,这种情感都是自由的,就像她的画面一样。

“枝上鸟”并不是本次展览最具代表性的作品,却与过去的作品保持着最直接的联系,也最能体现变化的线索。清脆的绿叶充满了画面,左边的叶子像是因为反射阳光而变得洁白明亮,也或者仅仅是处于视线的焦点之外,就在画面里淡出了。树叶的色彩变化并不符合自然常理,每一片都像是拥有了自己的性格,在不同的绿色间跳跃。其间的鸟儿更是如此,色彩丰富而干净,大概是来自童话世界的。它们的羽毛和树叶组成了完美的色彩搭配,似乎不应该仅仅是停留在那里,而是把这丛树叶当成了自己的家园,拥有一种群居在家里的闲适和安定感。在谢正莉过去的作品里,鸟类总是以标本的形式出现,在直线构成的架子里排列整齐,传递出被隐藏和重新唤起的活力。而这次,鸟直接飞上枝头,享受自然给予它们的一切恩惠,一切都变得开朗而柔和。另一幅作品名为“花与蛇”,蛇在花丛中隐约出现,带着暗藏的危险和自然的神秘,也从过去作品的瓶子里被放归自然了。

在其它作品里,盛开的鲜花无处不在。与过去的作品相比,新作品里出现了更明亮的色彩和更直接的笔触,画面的层次丰富起来,映衬了更加饱满的情绪。花的情感变化万千,粗略来说,唐人尚牡丹,宋人尚梅花;一个丰盈,暖香傲置;一个清瘦,寒英疏淡,基本概括了两种大的类别。谢正莉的画里有各种花卉,整体气质却更接近唐人的牡丹一些。画里的花也不是置于瓶中或者盆内的,没有“水冰清琉璃,横斜三四枝”那样的规矩,而是满山遍野地生长,颇有“忽如一夜春风来,千树万树梨花开”一般的随心所欲。然而,就像无数首吟唱花朵的古诗一样,花中的情感实在丰富,变化万千;既然是画花,每幅作品的情感自然也都有区别。谢正莉恰恰又是位情感丰富的画家,如前文所述,她对待画布又是如此诚实,所以,在每幅画的每笔色彩和每道痕迹里,都隐藏着她细腻而敏锐的情绪。有时是她在描绘花朵,而有时候,花朵大概也只是她那些难以言表的生命感受的载体而已。传说陈知玄幼年写过两句诗:“花开满枝红,花落万枝空”,看似平铺直叙,花的美好与无常,世间悲喜,成住坏空,都包含在里面了。谢正莉画中的花朵总在虚实之间,似乎也正应了它们的天性本身。

谢正莉是目前少见的,不照搬任何既有样式,反而还会被其他人模仿的年轻艺术家。因此,很多人讨论过她的个人风格。除了自身的气质与训练,在所受的影响方面,她也谈到过对诸如五代时期的徐熙,古代两河流域的雕塑艺术,以及古代壁画的喜爱。在笔者看来,她与马尔林.杜马斯具备一种深层而默契的相似性。杜马斯受到中国水墨的启发,在油画的直接笔触里找到了一种对物像的触摸感。这种“触摸”源自颜料本身的粘稠质地;不过,它绝不仅仅是技术上的,而是包括绘画意识形态的转变:对杜马斯来说,画中的物像并不是对任何实体的“再现”,而是通过触摸画布,赋予它自己的情绪,让画面具备另一种真实的存在感。画布上的物像不再是画面,而是某种有生命的存在本身[3]。这是杜马斯作品最为重要的意识基础。谢正莉也许并不了解杜马斯的创作逻辑,但她对宋代花鸟画,以及古代壁画的喜爱,并没有令她一味学习其中的技术和质感,而是让她的绘画发展出一种深层次的意识形态。这种意识来自她对时间和生命在画布上留下的不朽痕迹的感悟,让她相信其中的生命所在。这成为她的绘画方式的由来。于是,她也会去“触摸”画布,用尽自己当下的全部力量,并用此最直接的方式传递情感和体验。她和杜马斯似乎在各方面都是两位毫不相干的艺术家,但是,她们都在用画布丈量生命的宽度。了解了这一点,谢正莉过去那些关于形骸,死亡,或者时间的作品,才真正与盛开的鲜花置于同样的线索当中。这条线索不仅仅是情感的起伏流转,还有对画布一以贯之的天性,和不断努力后的自我确认,自我调整,以及逐渐的成熟。这也是本文开头提到的,“神韵”的由来。

和过去相比,这次的作品似乎显得甜美了一些。但是,如果说谢正莉过去的作品是把“哲思”的部分放在了画面可见的地方,那么在“常生”这个展览里,那些深邃的思考就和花朵一样,被转瞬即逝却又无限美好的风景隐藏起来了。就像季节的流转无需提醒一样,它们都依然在那里。当代艺术的潮流之一,就是一定要让人看见深沉的思考,这多少显得有些做作。那么,把自己对生活的一切所带来的,无比细腻的体验,还有对生命本身的热爱和冲动,加上那些时断时续的感动和悲伤,以及由此而来的,无比真诚的思索和冥想,都掩盖到盛开的花丛里,这些需要更大的理性,力量,与勇气。于是,作为年轻艺术家,谢正莉为我们呈现了她暂住花间的时刻。这一刻的出现,让我们愿意相信她所确信的一切。大美之路径不止一条,花间却必定有路通向那里,正如秦观那首著名的“点绛唇”: “醉漾轻舟,信流引到花深处。尘缘相误,无计花间住。烟水茫茫,千里斜阳暮。山无数,乱红如雨,不记来时路。”

————————————————

注1: 关于“亲密性(Intimacy)”的论述,见Groupe H3, Heterologies, Press Universitaires de Perpignan, 2006

注2: 译自丢勒(Albrecht Dürer)版画作品,原名“Melencolia I”, 1514年

注3: 关于杜马斯绘画的意识形态,见 Marlene Dumas – Measuring Your Own Grave, Cornelia Butler, MOCA.D.A.P, 2008

On Xie Zhengli's Recent Works From the 2010 solo exhibition Xie Zhengli, to the 2012 Shadow of Colors, till There And Ever today, paintings by Xie Zhengli have evinced texture and idiosyncrasy rarely seen in young artists these days. The idiosyncrasy does not come from imagery or subject matter after careful calculation; it comes from the unique way of painting in the constantly evolving themes. She first cautiously maps out things she would like to draw. Then she scrubs it, laboriously, and makes adjustments, again and again, until the objects on the canvas are “exhausted”, and turn into shadows of their own. This is not a process when things flow naturally; it is a little awkward, even clumsy. But it is the only way to achieve the certain kind of “aura” she has been looking for. People in ancient China believed in the saying that painters are to be found in their paintings. European scholars, on the other hand, prefer scholarly terms to figures of speech. They use the word intimacy to describe, in a word, the courage the painters demonstrate in giving their feelings and techniques up to the canvas. This word is a bit unwieldy, but it is particularly fitting in describing the paintings by Xie Zhengli, where not just her feelings and techniques, but also the whole strength of her body, and the fluctuations of her emotions, are all there on the canvas. In those traces left by the many scrubbings, we see what she loved, what she hated, and what she wanted to change but failed and eventually found a way around in a sudden inspiration. Even the length of her arm can be detected in the flow of the colors, light, and shadows. She is not the best in terms of techniques, but she is the most candid about techniques. She almost embraces her paintings when she paints. This candor gives her works limitlessness and room for growth. Based on this candor, Xie Zhengli has created her unique character, and has demonstrated maturation and self reflection for the past few years. This seems a natural process, but it is what many artists, including some so-called established ones, lack. In fact, this is the foundation for works to be genuinely appreciated, collated, and even studied. If the solo exhibition in 2010 was still raw, then the 2012 solo exhibition Shadow of Colors revealed the sharpness of her perception. She found inspiration in specimens, depicting animals on display. These exhibits had already lost their life, but were given by her a different kind of expression, a new life. It was not the life of individual animals, but was from the air that saturated the whole creation. This air, combined with the impassioned process when she created the works, turned the canvases into a place where life continued, instead of just producing the mere semblance. Back then, we could not easily envision the position these works in Shadow of Colors would eventually take in the entirety of her work; in other words, whether the inspiration from specimens was transient in nature. And these new works dissipate these doubts. Although the subject matter is this time flowers, they continue to focus on natural creations. More importantly, the paintings demonstrate vitality that is consistent, innate, and resilient. Even the canvases are given life, and bloom together with those flowers. If we may say that Shadow of Colors connotes tranquil meditation, or, as in the acclaimed engraving Melencolia I by Dürer, conveys melancholy about the unknown of death, There And Ever seems to be embracing the vibrancy of life. The painter has used passion that almost rises to the level of willfulness, and has discarded the melancholy of the past. Xie Zhengli was born in Chongqing. The park near her home was where she used to play around when she was young. In the year 2012, with the conclusion of her solo exhibition Shadow of Colors, she turned 30, when she went back to the park, and, out of pure coincidence, walked into a chrysanthemum fair of her age, the 30th. It seems to be something of an implication. She said, “I was born and raised here. When I left and returned, I found it was exactly the way I left it. Those memories are there to keep me company and give me warmth. After all those subjects of death, of skeletons in the remote past, and of the farewells to life, when I see these flowers again, I finally see through their exterior and down to the core of their existence, who open during the season of distress.”This becomes the inspiration for the chrysanthemums in her new works. There are similar stories behind other kinds of flowers as well. All in all, they are not just the products of observational drawings, but also include impressions all the flowers have made on Xie Zhengli. These impressions leave traces in her memory, just like the barely visible traces left on the canvas. Flowers wither, memories fade, but things that once existed will always be there. The vitality is distilled, and becomes an abstract power, merged with the power of the canvas. Ever since the ancient days, many among the literati loved flowers. Tao Yuanming loved chrysanthemums, Zhou Dunyi loved lotuses. They saw different characters in flowers, and they had different feelings for them. And if we have to find something in common about them, probably the only thing is that they all loved flowers. Why did they love flowers? The admiration for flowers found its foundation in the practice of offering flowers to worship the Buddha since the introduction of Buddhism into China, and reached its culmination in Song Dynasty when the vases became a treasure in studies. As for the root cause, it’s probable that flowers embody the beauty of nature and the law of life. Xie Zhengli does not excel at intentionally creating the elegance of the literati, but she possesses feelings for flowers that are long lasting and deeply etched. Whether it is in the ancient or modern days, this kind of feelings are free, like her paintings. Birds on the Branch is not the most typical of all the pieces on this show, but in it we find the deepest connection to her past works, and hints about the transition. Crispy green leaves fill the canvas. The leaves on the left are white and bright, possibly because of the sunlight reflected, or because it fades away outside the focus of attention. The variation of color among the leaves does not observe the common sense, and each leaf seems to possess its own character, switching among different kinds of green. All the more so, the birds among the leaves are rich in color and unblemished, probably coming from a wonderland. Their feathers match perfectly in color with the leaves, and it seems that this place is more than just a temporary stop for them; it is their home, and has this coziness and sense of security only living together at home would possess. In Xie Zhengli’s past works, birds appeared as specimens, arranged methodically on shelves comprised of straight lines, conveying vitality that had been hidden and was revived. This time, birds fly onto the branches, enjoying the bounty of nature, and everything becomes exuberant and soft. In another piece of work, Flowers and the Snake, a snake is hidden among the flowers, implying hidden danger and the mystery of nature, and it is also released into the nature from the jar that confined it in past works. In other pieces, blooming flowers are everywhere. Compared with past works, these new works have more bright colors and more assured brush strokes. There is more richness in color and depth of field, boasting a wealth of emotions. The feelings expressed by flowers are many. Roughly speaking, people in Tang Dynasty admired peonies, and in Song Dynasty people admired plum blossoms. One is plump, abounding in fragrance and placing itself on an exalted position; the other is lean, detached and uninvolved. Basically this covers the two major categories. In Xie Zhengli’s paintings, there is a variety of flowers, and the temperament is close to the peonies in Tang Dynasty. The flowers in the paintings are not bottled in vases or tubs. They do not submit themselves to rules, but grow wildly on the fields, with the free spirit as is described in the verse “it was as if a spring breeze had blown overnight, bringing pear blossoms to thousands of trees”. As are those countless poems that celebrate flowers, the feelings embodied in flowers are diverse; pictures of flowers, therefore, should also be distinct from each other in terms of the feelings they express. Xie Zhengli is precisely this kind of painters who are finely attuned to emotions and feelings. And, as discussed above, with her honesty in front of the canvas, in every color and every stroke in the painting, there hides her emotions of delicacy and sensitivity. Sometimes she is drawing flowers; sometimes, it’s possible that flowers are but an agent of her feelings about life that are impossible to be put into words. It’s said that when he was young, Chen Zhixuan wrote two verses: “when flowers bloom, it is all the redness; when they wither, it is all but nothingness.” It seems just banal description of everyday scenarios, but the beauty of flowers, the uncertainty of life, the better and the worse of life, the cycles of life, all appear to be intimated in this simple verse. The flowers in Xie Zhengli’s paintings dwell in the space between the real and the fictitious world, which possibly speaks of their nature. Xie Zhengli is one of the young artists rarely seen these days who do not imitate any existing pattern but can still find her own imitators. Therefore, many have discussed about her style. Besides her temperament and her training, with regards to the influence on her, she mentioned Xu Xi in Five Dynasties, the sculptures in Mesopotamia, and the murals from ancient time. In my opinion, she and Marlene Dumas have this deep and profound comparability. Dumas was inspired by the Chinese ink painting. She found in the direct brush strokes of oil painting a certain tangibility. This tangibility originates from the thick textured paint, but it is more than just technical. It also includes a change in the philosophy about painting. For Dumas, the objects in paintings are not reproduction of any object in reality; rather, through the tangibility, painters should lend feelings to the painted objects, giving the pictures a kind of authenticity in a different sense. The objects in the paintings are no longer just picture, but existence with their own life. This is the most important philosophical foundation for her works. Xie Zhengli may not know the logics behind the creative process of Dumas, but her fondness for bird-and-flower paintings from Song Dynasty and murals from ancient time doesn’t confine her to the studying of merely their techniques and texture. It also helps her paintings to develop a deep-seated philosophy, which comes from ruminations about the permanent trails left by time and life on the canvas, something that makes her believe that there lies life. This becomes the origin of her style. Therefore, she will also “palpate” the canvas, summoning all her strength, conveying her feelings and experience in this most direct form. She and Dumas seem to be different artists in every way, but they are both measuring the width of life with their paintings. By knowing this, we can hence put these blooming flowers and her previous works on shadows, death, and time in the same perspective. It is not just about the fluctuations of emotions, but also about the honesty in front of the canvas, about the self-confirmation, self-adjustment, and gradual maturation. This is also the root of the “aura” described in the beginning. Compared with her past works, this series of works seems a little bit more pleasing and agreeable. However, if we agree that the philosophy in her past works was placed where it could be seen, then this time, the philosophy is hidden behind the ephemeral but ravishing scenes, as those flowers are. They are always there, just as the transition of seasons does not need a reminder. One of the trends in modern art is that it has to make people see some sort of deep thinking, which is to some extent affected. Therefore, to take the delicate feelings and experiences in life, the love and passion about life, the moments for tenderness and sadness, and from them the thoughts of the most sincerity, to take them all to the bushes of blooming flowers and hide them within, it needs more rationality, strength, and courage. Hence, as a young artist, Xie Zhengli presents to us the moment when she temporarily lives among flowers. This moment makes us want to believe in what she believes in. The roads to grand beauty are more than just one, and there must be one among the flowers. As is the famous poem Rouged Lips by Qin Guan: Drunk, I let my light boat Along the river float, Seduced to the depth of the flowers. Not freed from worldly care, I cannot stay long here. The mist-veiled hill and rill Are steeped for miles and miles in the sun’s parting ray. From hill to hill The reds are falling in showers. I can’t remember my homeward way.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术