Realism for Painting Content and Nothingness for Bone Structure

2011-04-15 11:31:21

This oil painting of Wang Hongjian is named Yellow River from Heaven. In Chinese, it is “Tianxia Huanghe,” and it is thought-provoking. Speculating from its nuance, the title has a double meaning. If “tianxia” is interpreted to be a verbal phrase, it means “to tumble down.” It is quoted in Li Bai’s verse “The Yellow River descends from heaven.” If it is interpreted as a noun phrase, it refers to China as the land of the Yellow River. Wang Hongjian, who comes from Henan and has been nurtured by this river, naturally holds a deep feeling towards it. Most of the characters in his painting are countrymen of this land, and he dares to claim, “Who in China does not come from this yellow soil?” With such grandeur, the painter displays, besides realism, also his sense of mission that the Yellow River is still the cradle of Chinese civilization. This painting is expected to be one drop of water flowing to a new Han & Tang Dynasty along the Yellow River.

The scene in Yellow River from Heaven is ordinary but rarely seen nowadays: a wooden boat anchors alongside the shore, seven or eight porters come for unloading, some push and some pull, and they lift heavy grain sacks onto their backs, step by step walking out of the painting. Such a slow motion is called Yellow River from Heaven, a title which seems incongruous at first. But you will figure out that it is not the first time that a Wang Hongjian title bears this kind of mystery. The same slow motion can be traced back to his debut work The Founders in 1984, a painting about people carrying gigantic stones on Taihang Mountain, of which the content is similar to this painting. Apparently, Wang Hongjian has strong feelings towards manual delivery of loads. Yet it is called The Founders. So what is the nature of its foundation? The Great Wall? Or the palace? In one word, it is the foundation of culture and civilization. After all, Chinese culture of thousands of years has all been established on these sweating shoulders.

Last April, my wife and I left Switzerland and went to hike Huang Mountain. It was a weekend, and about twenty thousand tourists flocked there with cameras and mobile phones. It took about four hours to line up for the sky rail. Also, the straight narrow path with a hundred steps allows only one person to pass through at one time, which results a heavy bottleneck situation, where it can take another two hours. The sky rail is used only for tourists and all the non-natural materials, as big as paving stone blocks, furniture, doorframes, glass of restaurants, and as small as bottled water, films and souvenir, and also all the meals of visitors are carried uphill by porters on their shoulders. This practice of enormous physical labor was viewed as unbelievable and inhumane by the Swiss people who had sold the sky rails to us. The French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupery has described a trip over pyramids built up by the Peruvian Incas in Night Flight, and he moaned, “The king who gave an order to build a pyramid did not pity his people with their suffering, but rather man’s death; He did not care about individual death, but rather an ethnic group’s extinction. Because a civilization might be submerged within sand dunes one day, the pyramids piled up by huge stones are left as traces to expose man’s presence from all being buried in the desert.” These are words from the author of Little Prince, the twentieth-century French literature saint, a Western humanist who put corporate civilization over individual life and death. It is to our great surprise that his opinion is so close to Eastern thinking. Wang Hongjian, with the similar starting point of Antoine de Saint-Exupery, paints people with burdened bending backs and expresses great pity on the transience of people in eternity. He does not protest against the fate of these stone carriers, and does not demand to replace manual work with technology. However, he calls them “founders,” and at the same time shows his respect to these laborers who can never finish piling stones. The first founder in Chinese history was Emperor Qinshihuang. I believe that the Great Wall was built not only to prevent the invasion of alien races, but also with a profound meaning to demarcate a borderline for Chinese civilization, keeping the desert outside. This ideal is still actualized; the Great Wall has been the only manmade structure which can be clearly seen from the moon. Emperor Qingshihuang was cruel, but he used clay and stones to guarantee the continuity of a nation’s lifeblood. He was inhumane, but he was remarkably humane because he saw primitive emptiness behind civilization.

When we walked in the twilight from the Brightness Summit back to the North Sea, a young porter released his load and descended the mountain very fast. His figure viewed from behind seemed like a swordsman who can fly onto roofs and leap over walls. He was whirling, dancing and flying over the stone steps almost without tiptoeing on the ground, so swift and so free. Only after the experience of the tough time of ascending a mountain can one recognize the freedom of descending with no load. This freedom is different from the one we yearn for nowadays. We pursue individual freedom in order to break away from regulations and fulfill our self longings. However, the freedom of the porter is acquired through stone delivery, and he dares not overstep the boundary; with full care, he understands that it is a kind of mirage. A slight trespass will mean the loss of his freedom. “What old friends can you meet after the Yangguan Pass?” This verse shows that there is nothing but the desert beyond regulations, so this freedom is of no desire.

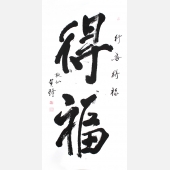

In talking about calligraphy, Dong Qichang once said, “You need to have oneness, which is no desire. No desire guides you to remain in stillness and nothingness as well as to take action in a right manner. The state of stillness and nothingness will enlighten you. The act of taking action in the right manner will lead you to the right principles. ” According to my understanding, “taking action in a right manner” means to use your brush correctly. “Stillness and nothingness” refer to a spiritual realm. Going through this realm can give perfect understanding, and this is the essence of enlightenment. So is painting. That is why Chinese water and ink painting has had an inseparable boundary with calligraphy since the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Both calligraphy and painting demand the use of brushes in the right ways to achieve certain principles and henceforth to present a spiritual realm. How to paint a spiritual space? In Dong Qichang’s words, it is first to remain in stillness and nothingness. Next, in a painting, paint what has to be there and leave the rest unpainted. For example, in traditional landscape painting, one paints mountains but not water, trees and humans but not clouds and mist. Not to paint means to leave a blank space. It is like watching Huangshan, misty and rainy, with mountains that fade away and show up from time to time. This is a good view that presents a spiritual realm. If the view is clear with great visibility, then there is no artistic flair at all. We color the mountains with ink and the unpainted water will surface, we paint a hillside to expose unpainted cloudy fog, and we carve a mountain peak that flies on the top blank paper. In this way, the painting has life.

This is the same principle with the game of Go to position enclosure strategies. An enclosure strategy is to work on an empty space, an empty territory to launch a combat. It begins with keeping the eyes away from the game board to construct a live buildup of the Go pieces. The game works on “the image of heaven and earth as square and circular as well as the principles derived from yin versus yang and action versus stillness.” It is a unique invention of China, in which players work on stationary pieces to create endless possibilities. In Dong’s ideas, it unfolds variations due to “stillness and nothingness.” Compared with Western chess, which originated from Persia, it is easy to distinguish the differences between Chinese and Western culture. Chess is to “take action in the right ways” through the pieces, with the intent to make advances. The entire Western culture, from ancient Greece, Rome to the Renaissance, is after all an “action-oriented” civilization and a culture of self confidence. The works of Michelangelo and Beethoven were humanity driven, which valued man as the center and with grandeur as the ideal. They could never have created such great works were they lacking in their absolute self-confidence. Conversely, Chinese culture is a modest one that places not human nature, but rather “nothingness” as the highest spiritual realm. The way to a rule a country centers on the principle of “not taking action,” just like to write in calligraphy with “no desire.” Even in Chinese literature, the most special personage Jia Baoyu has his last name “Jia” which means “not real,” as he was a stone before birth.

Wang Hongjian talks about the difference between Chinese and Western culture as “the West aims for the concrete, while Chinese nothingness.” This statement is most accurate. As an oil painter, he has to go for realistic methodologies by the Western tradition. Oil painting presents a contour with lines, the canvas with colors, and paintbrushes that cover everywhere, and there is no such concept as “the unpainted.” Wang Hongjian is a serious and steadfast painter, so he loves to paint stones and soil. It took him nearly one year to finish Yellow River from Heaven. He stayed in his studio painting every day, with no details overlooked. But he, after all, is a Chinese painter, and if you pay more attention to his paintings, you will notice that he focuses to inquire about Chinese aesthetic principles. To paint realistically is to ultimately paint “the unpainted.”

Just look at Yellow River from Heaven and you will realize that this painting portrays only water, not the sky. The horizon has been left outside the painting, with water to replace the sky. The color scheme is multi-leveled, showing the changeable colors of yellow soil. Because it is all one single color, it functions purely like Chinese ink. There are two distinctive primary colors in the centre painting: a blue cap, bright red underwear and red socks. If we say the color of yellow is equivalent to black ink in Chinese water painting, then red and blue are more like the blank unpainted zones of the painting. This technique serves to gather forces, which gives the painting more vibrant effects. The visual composition has both the realistic and nothingness. The real components mean the wooden boat and the personages, especially the heavy and full grain sacks. Nothingness means what is beyond the painting: the first left porter’s shiny bald head and the shadow near him, which probably might be the painter’s own shadow. These are strong evidences to indicate that the light source is from outside the painting. On the right, the stern has not been finished, and the porter is presented with only his half body, which hint the painting extends to what is beyond its frame.

Here, the artist employs the technique of “borrowed scenery” from Chinese garden landscape architecture, to open a hole on the wall and introduce an external view into a garden. The extension method and borrowed scenery are ways to illustrate “the unpainted” in painting. Just look at the motions of the seven porters—as if linked with each other in a serial manner. Three people shoulder their sacks on their backs; though loaded, they look like aquatic birds of a river to take flights. Oil painting, in general, does not demand to go into “a spiritual realm”; but this hovering motion, of turning weight into lightness, highlights the “spiritual realm” of this painting.

After one year of hard work, the painting was finally completed. The painter laid down his paintbrushes, turned over and looked at his burdened back bent personages, taking flights one after another. Then he went down the mountain empty-handed. Dong claims, “Take action in the right way to achieve certain principles. Remain still and retreat to nothingness in order to become enlightened. Go for rules and then enlightenment.” At this point, the painter has insights that encompass thousands of years. The unloading scenery at the Yellow River points to a recurrent and an unaltered theme from ancient times, so is the painting entitled Yellow River from Heaven.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术