Cai Guo-Qiang

2011-04-15 11:31:21

In his multifaceted, provocative, and open-ended art, an explosion is a creative act and the weight of tradition can be liberating.

Although Cai Guo-Qiang calls New York home, he’s not often to be found there. An international figure who receives a seemingly endless stream of museum commissions and biennial invitations, the 53-year-old Chinese-born Cai is one of the most peripatetic artists working today. I’m lucky enough to catch him between journeys, spending time in his downtown studio. He’s just been in Taipei, where he created, for New Year’s Eve, one of his carefully orchestrated fireworks displays, which he calls "explosion events." In a few days he will head to Doha, to visit the Arab Museum of Modern Art, which has invited him to do a solo show that will open later this year. All this follows exhibitions and installations over the past year in cities as far-flung as Mexico City, Nice, and Sydney.

For the past several decades, working at a pace that most other artists would find hard to match, Cai has been making and showing his politically inflected, site-specific installations and explosions. In 1993 he extended the Great Wall of China with a six-mile line of gunpowder that he detonated at twilight to spectacular effect. For "Fallen Blossoms," 2009, he installed a giant flower formed of gunpowder fuse on the Neoclassical façade of the Philadelphia Museum of Art . The blossom was ignited, erupted into a quick but powerful explosion, and quickly burned out. Its brief existence was captured on video and in photographs that were shown inside the museum, while a related installation of gunpowder drawings was presented across town, at the Fabric Workshop. Cai is a master at fashioning such moments of ephemeral and terrifying beauty, which are often freighted with multiple themes: the transience of life, violence, creation, mysticism, and materialism, even the patterns of the universe.

Big art that aims for big ideas is not easily produced within four walls, and Cai’s studio is not a traditional work space. Instead it is a place "to contemplate my creative direction, figure out my thoughts," he says, speaking through an interpreter. It also functions as a sort of hub or anchor: "No matter where I am in the world, I’m always working with the studio — a bit like a kite flying in the sky that always has a string, and the studio is the string." Further, Cai having opted not to work with a commercial gallery, his staff of 10 handles everything from coordinating his travel and the logistical complexities of the explosion events to producing exhibition catalogues to selling his finished works. "In a way the studio has become my agent," he says.

Cai has lived in New York since 1995. Over the years he has worked in several different sites in the city, including his apartment; he moved to his current studio, in the East Village, in 2003. The sprawling floor plan offers a few separate offices, the largest and most open of which is where the artist and his translator meet with me at a glass-topped table. Tall and lean and clad in a dark sweater and chinos, Cai conveys a personal warmth despite the formality of our mediated conversation. Assistants come and go, and the aroma of lunch being prepared wafts from the kitchen, where each afternoon the staff eats together, sometimes joined by guests. On display are posters for Cai’s many museum shows, along with a couple of his large gunpowder drawings. He lays out the designs, which are cut out with the assistance of volunteers (often art students) to form stencils. These are laid on Japanese hemp-paper panels and the artist applies various grades of gunpowder over the whole thing. The stencils are lifted and the powder ignited. The smoke and fire from the explosion create the composition, which is preserved by the assistants, who race in after each incendiary event to tamp down the flames.

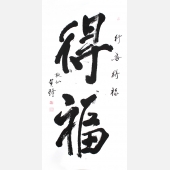

Cai likes the contingency of the process as well as its social aspect. The idea of the collective has never been far from his thinking. Born in the southern port city of Quanzhou, he grew up during the Cultural Revolution. His father ran a bookstore where high-ranking party officials could access forbidden Western literature by such writers as Samuel Beckett and Jack Kerouac, and the elder Cai brought home copies of "Waiting for Godot" and "On the Road" for his son to consume. The father also practiced calligraphy and traditional ink painting, two ancient forms that have influenced the son. Cai first studied at the Shanghai Drama Institute, but he eventually gravitated to visual art. In 1986, eager to leave China, he went to Japan on a student visa and stayed for nine years. He then came to New York for a yearlong residency at PS 1 Contemporary Art Center and decided to stay.

By the mid 1980s Cai was using gunpowder regularly, and it has become his signature material. He’s drawn to it for its myriad associations — although his fireworks are most immediately read as signifiers of Chinese culture, Cai believes they can transcend national boundaries. Indeed he typically makes a point of alluding to the city or region where his exhibitions are presented. In the solo show "Sunshine and Solitude," on view through March 27 at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), in Mexico City, a gallery floor is covered with volcanic pebbles surrounding a pond shaped like Texcoco Lake, where the city was first established, and filled with mescal, a pungent liquor made from the maguey plant with an evocative aroma (in a similar installation, at the Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain in Nice, the liquid was olive oil). Covering the gallery walls are 14 gunpowder drawings depicting the Mexican landscape and cultural motifs, and, in one panel, a black sun.

Cai’s gunpowder pictures are also performances. Last October, in preparation for a 42-panel commission for the new Arts of Asia galleries at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Houston, the artist set up a studio in a massive warehouse where, with a crew of volunteers, he created the 162-by-10-foot "Odyssey." For two days the public could watch him apply the gunpowder to the panels and the powder explode. The work, Cai’s largest gunpowder piece so far, is now a permanent installation at the MFA.

Production value can be high. In Cai’s 2008 retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York, a version of "Inopportune Stage I" comprising nine white automobiles emitting neon "sparks" was suspended inside the museum’s famous rotunda. The spectacle and scale of such multisensory works sometimes obscures their political content, which is not always overtly expressed to begin with. Art, Cai stresses, is not a means of exposing "the rights and wrongs of politics but rather reflects some of the complications of our time."

Last September he organized an exhibition called "Peasant Da Vincis" that presented the inventions of ordinary Chinese citizens. The show, at the Rockbund Museum, in Shanghai, was timed to coincide with the World Expo, which celebrates corporate ingenuity. "You don’t see the creations of real people" in the expo, he points out. "So I portrayed the individual creativity and expressiveness of the Chinese people."

Cai’s most populist endeavor was his contribution to the opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing: a series of footprint-shaped fireworks that traversed the city and ended at the Bird’s Nest stadium. "The government had a political agenda — to show the progress of the country," he explains. "So how does an artist find an interesting way to express himself through such a work of art?" One way is to think of the footprints as those not only of the many but also of a single individual, and it is the artist who walks the line.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术