The Painter Who Adored Women

2011-04-15 11:33:10

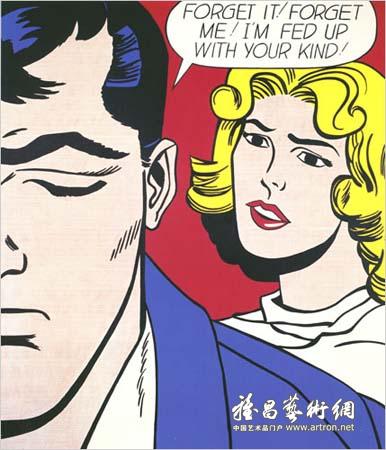

“Forget It! Forget Me!” (1962) by Roy Lichtenstein

“Roy Lichtenstein: Girls,” at the Gagosian Gallery, presents 12 of Lichtenstein’s early paintings of the female creatures otherwise known as women. Based on cartoons and mostly blond, they are anonymous, beautiful and often unhappily bothered, usually by men. Or, if you like, by boys.

Title aside, the show is terrific. Just when you thought you’d seen enough Pop Art to last a lifetime, this selection proves otherwise. It reveals Lichtenstein honing his indelible yet impersonal style, and it can be seen in one of New York’s most painting-friendly architectural settings. And ultimately only an ogre would deny that Lichtenstein’s portrayals in some way glorify the American woman by giving innocuous images of her generic concocted self and her roiling emotions such blazing formal power.

After all, as Dorothy Lichtenstein, the artist’s widow, remarks in an interview in the show’s catalog, “Roy adored women.” And the anonymity of his subjects has exceptions. The smiling woman in “Sound of Music” is clearly Julie Andrews about to burst into song as musical notes stream through the window — although her cheer is undercut by the sharp black shadow that divides her face into areas of red and blue, not unlike the stripe of green in Matisse’s Fauve portrait of his wife in a hat.

These paintings are themselves bursts, hot flashes of composition, America, humor and color galvanized and made one by pictorial intelligence. Because their visual machinations are perfectly obvious, they make normally arcane terms like form and formalism exhilaratingly accessible. Basically we watch them work.

Mrs. Lichtenstein notes that Lichtenstein painted on an easel that allowed him to turn each canvas so he could be sure that its power operated in all orientations. It had to work abstractly, in other words, in a way that couldn’t be missed.

Dating from 1962, 1963 and primarily 1964, the cartoon-based images here are dominated by industrial-strength red, yellow and blue, generously contoured with black lines. The onslaught of color and the seeming dumbness of the images are interrupted by the black-on-white balloons of speech or thought (or, sometimes, music), which have a complex visual and cognitive role in the Garbo-talks vein.

The paintings that lack them can seem too mute, but stillness is their point. In “Blonde Waiting,” you feel the seconds tick against the silence as a woman with an Angie Dickinsonesque mop of yellow hair intently watches a yellow alarm clock beside a yellow bedstead, wondering just how late Mr. Right is going to be. The silence turns film noir in “Little Aloha,” where the main colors are black and dark blue and one of Lichtenstein’s few nonblondes casts a come-hither look from the shadows.

But even without the balloons or musical notes, white is an essential element in these paintings. It is visible in highlights, like the woman’s tears of happiness in “Kiss V,” a compact, nearly quartered composition that must have benefited especially from Lichtenstein’s rotating easel. But mainly white is filtered through the scrims of Ben-Day dots. Lichtenstein’s cultivation and manipulation of the dot pattern is one of the show’s main subtexts.

In the earliest works here — “Forget It! Forget Me!,” “Little Aloha” and even the classic “Masterpiece” (where the female lead speaks the prophetic words “Why, Brad darling, this painting is a masterpiece!”) — the dots are faint and uneven, not quite pulling their weight. But they quickly gain size and substance and diversify. For example, women’s lips are often rendered not in solid red but in Ben-Day stars, stripes or little bow-tie shapes that stand out from the Ben-Day dots of the faces.

The Ben-Day dots allow Lichtenstein’s painting to look both more and less artificial. They signify mechanical reproduction, but they also add suggestions of light and reflection, shifting colors and variations in touch. The reflections would eventually lead to Lichtenstein’s many portrayals of mirrors, but first they seem to have spawned ceramic sculptures and works in porcelain enamel on steel, a small selection of which is included in the Gagosian show. On their shiny surfaces, fake reflections and shadows — like the aggressive, tattoolike scattering of Ben-Day dots on “Head With Red Shadow” — compete with real ones.

Mrs. Lichtenstein’s catalog interviewer is, perhaps appropriately, the latter-day Pop artist Jeff Koons, who as usual alternates a golly-gee robotic air with genuine perceptions. Sometimes he blends the two, as when he says: “I always loved how Roy’s work really challenges life force because it tries to compete with life force in the realm of the artificial. He would try to have the artificial keep up and challenge the power of life.”

This is another museum-quality show from Larry Gagosian’s gallery, and, as is often the case here, everything has a double function, like serving up artists that any dealer would like to represent. Not only is there Mr. Koons’s interview with Mrs. Lichtenstein; Richard Prince, who just left the Gladstone Gallery and is about to have a show at Mr. Gagosian’s gallery in Rome, contributes a small inserted brochure. It juxtaposes each of 22 steamy pulp-fiction covers of books (all titled with female first names) with a Lichtenstein woman painting. The illustrations of scantily clad, curvaceous femme fatales would seem to be the last thing Lichtenstein had in mind.

What he had in mind was form, a transformation of the terms of real and fake that, as Mr. Koons suggests, was beyond either, a thing in itself. This show makes especially clear how Lichtenstein’s work functions as a kind of primer in looking at and understanding the grand fiction of painting: the thought it requires, its mechanics, its final simplicity and strangeness. These great paintings convey all this in a flash of pleasure, compounded by the thrill of understanding.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术