The Prowess of the Painter in a Hunter's Paradise

2011-04-15 11:33:10

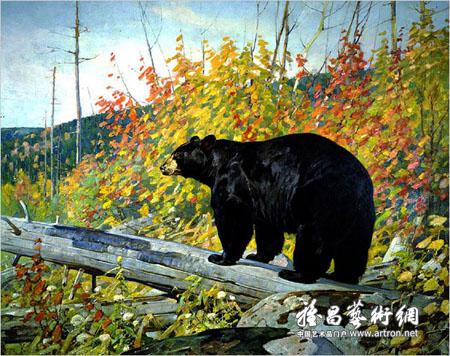

Rungius's "American Black Bear" (1929)

Nearly every car here has Wyoming license plates, but you can tell which are not driven by locals. Like mine, they hurriedly pull to the side of the road or even stop dead center, their drivers gawking as thunderously dumb-looking bison amble alongside. At dusk a moose brings traffic to a standstill by grazing on a shrub.

Wildlife seen through a car window may not appear terribly wild, but its presence is one reason that here, where the snow-covered rock faces of the Tetons loom over a flat grazing plain for pronghorn antelope, elk and bison, the National Museum of Wildlife Art was built in 1994. It is meant to seem part of the animals’ habitat, as if carved out of a hillside above a highway, outdoor sculptures keeping company with their models. In 51,000 square feet every painting, drawing and sculpture is of wild animals; one gallery is devoted to buffalo alone. If we are ready to brake in amazement at glimpses of the real, why not join the 80,000 annual visitors to this museum to see how the real is imagined, how vultures, bears and bison have been evoked in paint, ink or bronze?

But “wildlife art” is a peculiar genre. Lovers of fruit salad and floral bouquets are not the main audiences for still lifes, yet animal lovers are not only the patrons of this genre but also its creators. The point of wildlife art is its subject, and the uneven quality of some of these works — even by well-known wildlife artists — shows an impulse other than the purely aesthetic at work. Realism is the dominant style, and kitsch is the familiar currency.

Surely the 19th-century painter William Holbrook Beard — who specialized in anthropomorphized animals — meant to be comic in his painting “So You Wanna Get Married, Eh?,” in which two young bears bashfully approach the village elder for permission, but now the image is almost campily creepy. An exhibition devoted to the German-born wildlife artist Carl Rungius (1869-1959) has more than its fair share of artificial, italicized colors or stiff creatures that seem pasted in place. A traveling show of the contemporary wildlife artist Robert Bateman, contains some haunting images, but many reveal an almost sentimental yearning for the snows, fields and forests of creaturely life. Unvarying homage is paid to animals’ nobility; they seem conceptually tamed, leaving little that is unkempt or truly wild.

Yet weaknesses don’t matter much. You come into this museum from the roads or hiking paths (or, in season, perhaps, the hunt), expecting and desiring something quite different from what might be offered, say, by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This doesn’t mean that the museum always falls short of aesthetic expectations. It may embrace too widely, but it can also touch deeply. The explanatory texts and presentation by the curator, Adam Duncan Harris, are informative, the presentation intelligent.

The paintings in one gallery gently probe the relationship between humans and animals (thus giving Beard an intriguing context). Another shows Picasso’s prints for Buffon’s great 18th-century natural history, in which vultures, for example, are described as having “the lowest instincts of greediness and voracity,” as being “robbers rather than warriors,” descriptions that inspired Picasso voraciously to thrust with thick inky jabs, his rapacious bird standing on a black offalic mound.

Art, though, is not the main point. The museum embodies an impulse that is more powerful than the sum of its parts, and it is more easily felt here, just above the National Elk Refuge and near Grand Teton National Park, than it could ever be in, for example, the wilds of New York City.

In his illuminating book “American Wildlife Art” David J. Wagner argues that the painting of wildlife developed in a far different manner in North America than in Europe. England, he points out, had a tradition of “sporting art,” including images of the hunt, or paintings that focus on “species often targeted as game by sportsmen.” Another tradition of animal painting was the scientific: the attempt to catalog species visually. Sporting art and zoological art tend to domesticate their subjects, showing animals as the objects of human ritual in one, or isolating them from their surroundings in the other — even using taxidermist’s specimens as models.

But something remarkable happened in the 19th century in the New World. The wild, which had become largely alien to everyday European experience, was here commonplace, particularly in the West. European paintings tended to show exotic animals in zoos or decorous landscapes; here similar creatures seemed to wander freely, without bounds.

In Europe hunting was traditionally controlled by landowners; the hunt was highly ritualized and associated with class hierarchies. In the United States, particularly in the West, hunting took on opposing associations: it was linked to populism and freedom from constraint.

I am painting with too-broad strokes, but such ideas of wildlife reflected an idealized vision of democratic man and his possibilities. Hunting was imagined not as a conquest of nature but as participation in it. In this sense wildlife art may be a distinctively American genre.

It is astonishing how many wildlife artists were drawn to the United States for these very reasons. The exhibition explains that Rungius came here to hunt moose; when he went west in 1895, "he experienced a freedom to hunt and explore unavailable in Germany." Another pioneering wildlife artist, Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, has the distinction, according to Mr. Wagner’s book, of having shot the last bull moose in the Adirondacks in 1861.

But the hunt did not inspire "sporting art"; despite the overlap between hunters and painters, the hunt and its bloody aftermath is not the genre’s subject. With some sleight of hand, the goal was a kind of wilderness pastoral, portraying an unbounded world in which humanity was about to make its home.

There is some fantasy in this, a simplification that can lead the way into kitsch. But if taxidermy, hunting and painting are modes of capture, they are also modes of tribute. The moose heads mounted on walls or sold for thousands of dollars in souvenir shops in Jackson are affirmations of the hunter’s power and prowess. But like many paintings at this museum they are also monuments to a particular kind of encounter with the wild, in the wild. Environmentalism and hunting and painting become strange bedfellows.

I feel their shared impulse most intensely, not by encountering wildlife, but by hiking in Grand Teton National Park. The snows are still on the paths, 8,500 feet above sea level, and boots slip from side to side, or plunge, unexpectedly, where rushing streams have carved spaces around boulders and glacial moraine. Around each turn of a snaking path I cannot help but gasp at the immensity, an expanse of rock and melting ice, chasms and rushing waters, pines and shattered stones. I keep pausing, trying to capture a slice of the vista with a camera, knowing that what I will end up with instead is a faint echo of the experience, a reminder rather than a replica.

I feel the foolhardiness again in Yellowstone National Park, where the bleak devastation of 1988 forest fires creates an otherworldly backdrop to blue mists rising from hot springs and geysers. I snap away with each gasp, knowing the futility of it and hoping at least to commemorate the encounter. That is the impulse behind the museum and much of its art. And it is one, I confess, that lies behind this column as well.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术