Art Makes Such Weird Bedfellows

2011-04-15 11:33:10

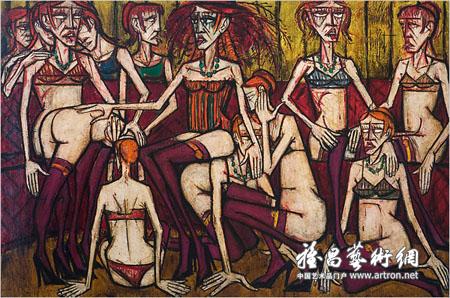

Pretty Ugly The group exhibition, split between Gavin Brown's Enterprise and the Maccarone Gallery, features works from about 75 artists, including Bernard Buffet's "Les Folles."

Everyone-into-the-pool gallery group shows are always a welcome distraction in a steamy New York midsummer, even when the water is tepid and unsightly matter floats to the top, as is the case in “Pretty Ugly,” a group exhibition split between Gavin Brown’s Enterprise and the Maccarone Gallery.

There are about 75 artists on the guest list, though it feels like a cast of thousands, so logic-defying is the lineup. Hannah Wilke rubs shoulders with Marsden Hartley, and both press flesh with Elizabeth Peyton, Rudolph Schwarzkogler and Bruce LaBruce.

Like most art world shindigs, this is an intensely networked affair. Lots of best friends of friends — artists who are the partners of curators, who are planning retrospectives of other artists, who are represented by the galleries presenting the show — along with a few bused-in oddballs (two Stanislaws, Szukalski and Witkiewicz) and recruits from the modernist mothball brigade (Pierre Alechinsky, Bernard Buffet).

Summer shows of this kind can be newsy; they can indicate shifts in direction in art that will unroll in the season ahead. But this one doesn’t feel that way. In fact it feels a little old. Its basic premise is that our ideas of beauty in art are changing, but we’ve known that for years. Pretty and ugly have been the twin poles of contemporary figure painting for ages now. Merged together — and they are always merging — they turn into weird. And weirdness is, basically, what “Pretty Ugly” is about.

Also, the show has been done before, in a way. Its organizer, Alison Gingeras, an adjunct curator at the Guggenheim Museum, used to work at the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris. There, in 2003, she produced an exhibition called “Dear Painter, Paint Me: Painting the Figure Since Late Picabia.” “Pretty Ugly” seems to have been modeled on it, but with sculptures, photographs and flower paintings added.

An installation of such paintings across a front wall at Maccarone establishes a couple of things: first, the show as a whole will be organized by themes; and second, it will be an old-new mix. In the floral lineup we find a 1918 Abraham Walkowitz still life next to Andy Warhol’s 1964 poppies along with Mark Grotjahn’s “Angry Flower (Big Nose, Baby Moose)” (2003), all bracketed by Takashi Murakami smiley faces from just last year.

This reads like a provocative combo, but on the wall it doesn’t add up to much. None of the works are refreshed, illuminated or deepened by the company they keep, which should be the point. On the plus side Mr. Grotjahn’s painting of what looks like the face of Bruce Vilanch blooming out of a cabbage rose is some kind of revelation. Who knew that this artist of catchy but formulaic starbursts could get so nuts?

A couple of sections have chromatic themes. The “Pink and/or Gold Room,” a sort of shrine to winsome-weird, has a painting of a baronial hall in fuchsia by Karen Kilimnik, an Otto Muehl bronze-gold monochrome and a partly pink collage by Laura Owens with the word “failure” writ large.

In the adjoining “Shades of Green Room” you will find a bile-green Picabia; a minty Anselm Reyle; and an undulant landscape by Edward Middleton Manigault (1887-1922) that refuses to come into focus no matter how hard you blink and squint. It looks like it was meant to be viewed through 3-D lenses. (Manigault went on fasts in the hope of sharpening his color sense and eventually starved himself to death.)

The two Stanislaws are in a gallery called the “Head Room” and, between them, they suck up a good amount of psychic air. Stanislaw Witkiewicz (1889-1939), who is represented by three scary-weird little drawings, ingested tons of drugs, wrote a book called “Insatiability” and priced his portraits according to how much he distorted his sitters’ features.

The sculptor Stanislaw Szukalski (1893-1987), also from Poland, was an art star in his day, so highly regarded that, when he was at mid-career, the Polish government erected a museum in his honor. When the building was leveled by German planes in 1939, Szukalski fled to the United States and settled in Burbank, Calif.

Although he lived in obscurity there, he was not inactive. Among other things he formulated a universalist theory of history called Zermatism, based on the premise that all human life originated on Easter Island, that Polish was the source of all languages, and that a race of malevolent Yetis was destroying civilization as we know it.

His freely espoused aesthetic and political views gained attention in California cultural circles: he was as rabidly anti-Picasso as he was pro-Ronald Reagan and regarded art critics as the scum of the earth. The attraction of his neo-Symbolist sculpture — a life-size bronze bust in the show of the Polish military hero Bor Komorowski looks like a sad-eyed Darth Vader — is harder to fathom.

How did this artist find his way onto the “Pretty Ugly” A list? It couldn’t have hurt that R. Crumb was an early advocate and Leonardo DiCaprio an avid collector. And Szukalski is in his element here, mingling with contemporary maverick types like Roberto Cuoghi, Mark Flood, Llyn Foulkes and Stan VanDerBeek, not to mention the distinctly un-maverick Bernard Buffet (1928-99).

Buffet’s art is routinely dismissed as skillful but facile, which it is. But a lot of painting is now, so he fits in neatly here. And Ms. Gingeras, who seems to be a fan (he was in her Paris show too), gives him two center-stage moments at Gavin Brown, where a mural-size Buffet painting of “Cabaret”-style artistes dominates one room, and a skeletal figure of death — painted the year Buffet died, a suicide — rules another.

One reason these pictures make an impression here is because so little else does. Despite some offbeat choices too much of the work at Gavin Brown is predictable: multiple Kilimniks, Murakamis and Picabias take up space that might have been given to less familiar fare. Can’t Paul McCarthy and Martin Kippenberger have been given a rest? And how many Hans Bellmers do you need to make a pretty-ugly point?

In the end the problem with “Pretty Ugly” isn’t that it celebrates weirdness, but that it stops at weirdness. And weird is too easy, too obvious, too thin. Like Surrealism, which is weirdness psychologized and academicized, it delivers a quick thrill but ends up being a snore.

I was glad to spend a summer afternoon poolside with the “Pretty Ugly” crew, ruffling brackish water, pushing flotsam around. But the art establishment’s vacation should be over now. It has gone on too long. And artists, caught up in a New York market that prospers from a million little weirdnesses, should take a head-clearing plunge back into work and see if there aren’t some other ways to go. Weird can be cool; it can be powerful. (The paintings of John Currin and Peter Saul are good examples.) But as an end-in-itself exercise, which is what this show looks like, it’s a waste of time.

黄琦

黄琦 测试用艺术

测试用艺术